An Exemplary Course

- Caroline Bruzelius

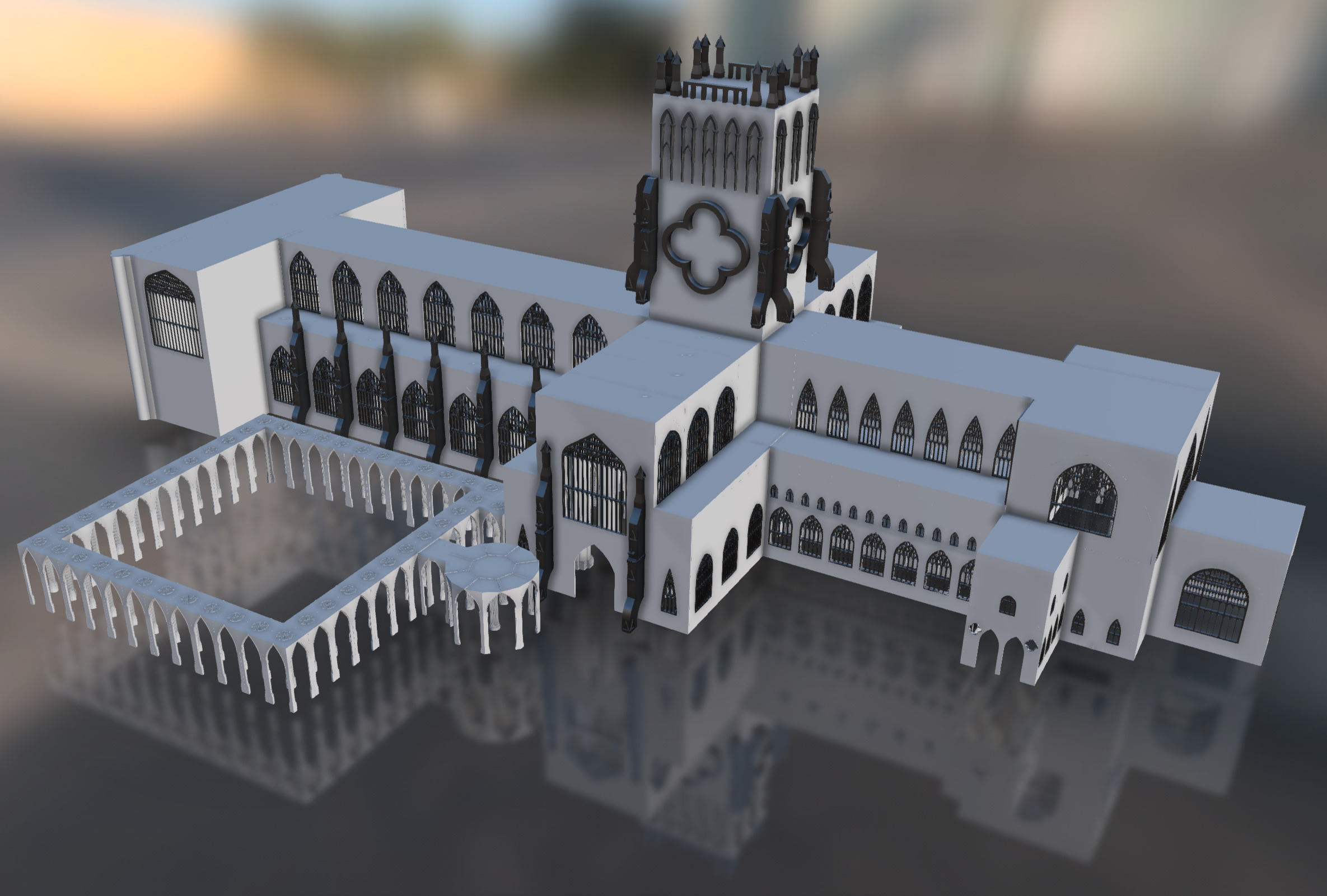

The Wired! Lab experience emerged from one course taught at Duke University that began with my arrival at Duke in 1981: Gothic Cathedrals. Because it attracted students from numerous disciplines (Biology, Political Science, and Economics, for example), it was hard to assign a meaningful research topic, so, instead, I developed a new type of assignment: a fictional cathedral with an “historical” narrative and design that included a ground plan, façade, elevation, section, and full decorative program.

Students were encouraged to be as original as possible, while at the same time respecting historical facts, regional styles, and locally available materials. These new cathedrals had to “stand up in a strong wind,” so vaults and buttressing needed to be structurally sound. Each team also had to produce a budget, estimating sources of income (taxing peasants was always a favorite), and the costs and scale of the labor force. At the end of the semester, projects were presented in front of a jury of colleagues and graduate students and prizes were awarded by a dean, the provost, and once even then-president of Duke, Richard Brodhead.

Students were encouraged to be as original as possible, while at the same time respecting historical facts, regional styles, and locally available materials. These new cathedrals had to “stand up in a strong wind.”

How did technology get into the picture? Around 2002 I decided to try having students produce their design components using AutoCad, and the results were spectacular. Instead of pencil drawings, we had professional renderings of façades, ground plans, sections, and elevations; the integration of computer-aided design exponentially raised the level of the visual components of the project. That “floated” the other components upwards: the historical narrative, the decorative program, and budget and labor projections were produced with new levels of professionalism.

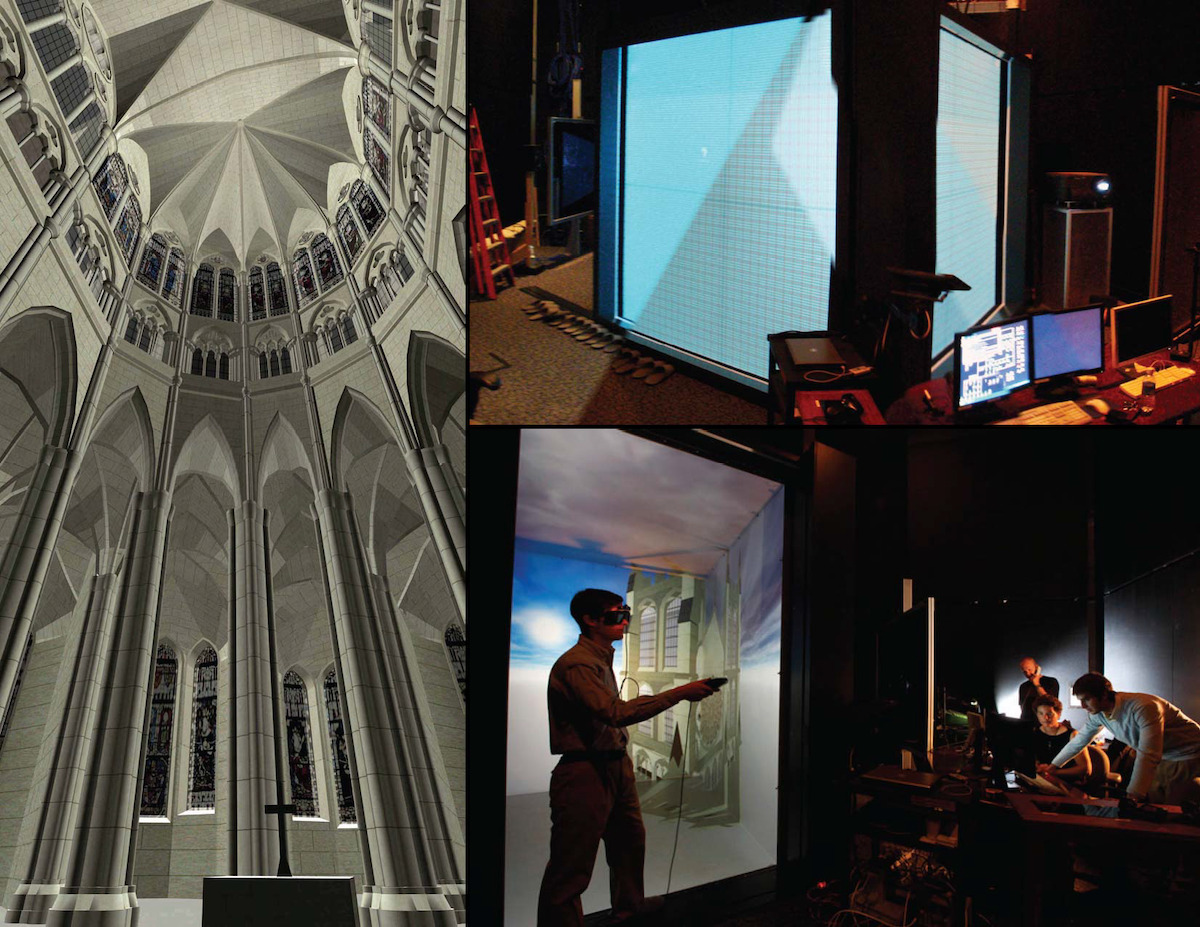

With this experience in mind, and with new faculty brought into the department as part of the Mellon-funded Visual Studies Initiative, I began to talk with a new colleague, Rachael Brady, whose primary appointment was in Engineering. We transferred one cathedral design (by Charles Sparkman, Duke ’09) into Unity to present in the Duke Immersive Virtual Environment (DiVE): now a student-designed cathedral could be experienced as real space.

Rachael and I considered whether we might engage in other projects and found a common interest in the topic of representing time: could new digital tools enable us to narrate time and change in buildings and cities? Could we develop a narrative form that could tell stories about how the spaces and places of the past were repeatedly transformed? As a result of our experience in the Gothic Cathedrals course, in 2008 we began to plan an experimental course that would test the potential of digital visualization tools for historical topics. We roped in several colleagues—Sheila Dillon, Mark J. V. Olson, and Raquel Salvatella de Prada—along the way, and offered a course, Wired! New Representational Technologies, in Spring 2009 where we modeled the construction phases of a medieval monastery near Naples, San Francesco a Folloni; the construction of Santa Croce I in Florence; and the architecture and sculptural decoration of the ancient bath at Aphrodisias in Turkey, among other projects. We were so enthused we baptized our new initiative “Wired!”

Technology changes everything: the questions that art historians ask of their evidence, the ways we communicate narratives about time and process in cities and buildings, and the capacities of digital tools to generate new knowledge.

Technology changes everything: the questions that art historians ask of their evidence, the ways we communicate narratives about time and process in cities and buildings, and the capacities of digital tools to generate new knowledge. Digital technology presented a bright future in our fields, and we had a responsibility to our students as well as to the discipline to keep exploring. It was a decisive moment, and there was no going back to traditional art history.

And that is exactly what the Wired! team has done for the past ten years.

Banner Image: Ground plans and elevations for a hypothetical gothic cathedral by Charles Sparkman (Duke, ‘09).