Objects

- Paul B. Jaskot

- Mark J. V. Olson

The fundamental subject of Art History and Visual Culture is inevitably the object. The work of art, the artifact, the building, the sculpture, the ceramic pot, the orphan photograph—the list of possible cultural objects is vast and infinitely varied, drawing us to their study as keys to exploring the great range of human creativity. Computational methods and digital visualizations have provided a unique and exciting way to analyze objects anew in order to raise new research questions and new analytic conclusions in Art History and Visual Culture.

Obviously, the object has not always been the center of culture analysis. For example, early Art History was much more likely to focus on the biography of the artist, and even in the opening of the twentieth century one could more easily find scholarship studying connoisseurship or the typological nature of artworks rather than their individual qualities or meanings. Yet, over the course of the last century, the focus on cultural objects as individual works worth studying has more and more taken center stage. Our scholarly work has contributed to this tradition and has added new methodological approaches with digital technologies that have pushed our understanding of cultural objects in new ways.

While it has been feared that the digital distracts attention from, or worse, completely displaces the need to study physical objects firsthand, our experience has been the opposite.

While it has been feared that the digital distracts attention from, or worse, completely displaces the need to study physical objects firsthand, our experience has been the opposite. On the one hand, the perceptual registers opened up by computation can yield new insights and pose new questions about the “thinginess of things:” their material composition, the conditions and techniques of their production, and their connection to other artifacts. On the other hand, and often simultaneously, any attempt to render digital an object confronts that object’s recalcitrant materiality and the inherent limitations of being digitally sampled or translated into a strict algorithmic logic. As such, the analytics place the object and its computational surrogate in a productive dialectic that foregrounds the materiality of both.

The thematic focus on the object as artistic or cultural evidence has led to a rich range of questions and approaches in the work of lab faculty, staff, and students. In Digital Athens, for example, constructing a database of the individual remains of sculpture in the Agora has led to thinking about the transient meanings of sculpture and change over time. Conversely, a focus on individual works of art and buildings in the Venice initiatives, as exemplified in such projects as the A Portrait of Venice exhibition related to the de’ Barbari View of Venice (1500), has shown how a close concentration on a single work of art using digital methods, in particular the wooden blocks that were used to print the woodcut, can lead to an entirely new understanding of the object and the city itself. Digital methods have also been used by our teams to visualize the complexities of objects in new ways.

Digital methods have also been used by our teams to visualize the complexities of objects in new ways.

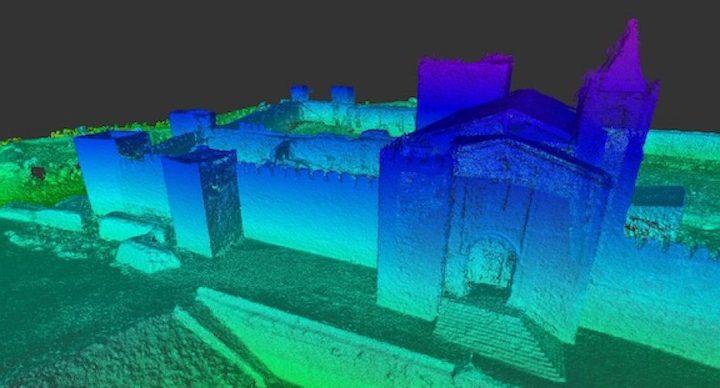

The Book of Fortresses project has shown the extraordinary finds that can be made by using digital means to visualize the spatial views of the important early modern Portuguese Livro das Fortalezas, even as the project lays bare the limitations of Cartesian perspectivalism embedded deep into the fabric of contemporary geospatial and 3D visualization tools.

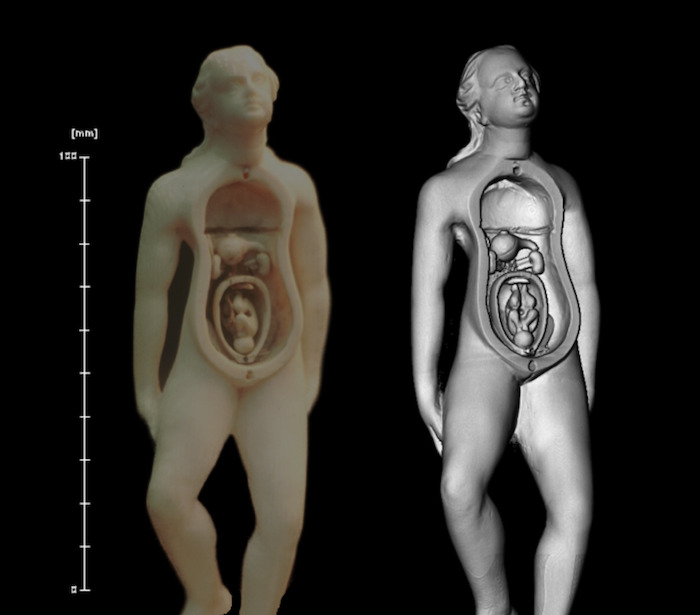

In a very different vein, the Operating Archives project has used 3D modeling to balance questions of preservation with the analytic need to physically explore Duke’s rare collection of ivory anatomical models. In all of these cases, the centrality of the object as both the subject of study as well as the means of expanding other cultural questions has proven productive.

The lab’s foundational concern with change over time has led to a sustained engagement with the storied “lives of things” and to fascinating new ways of telling digital stories about works

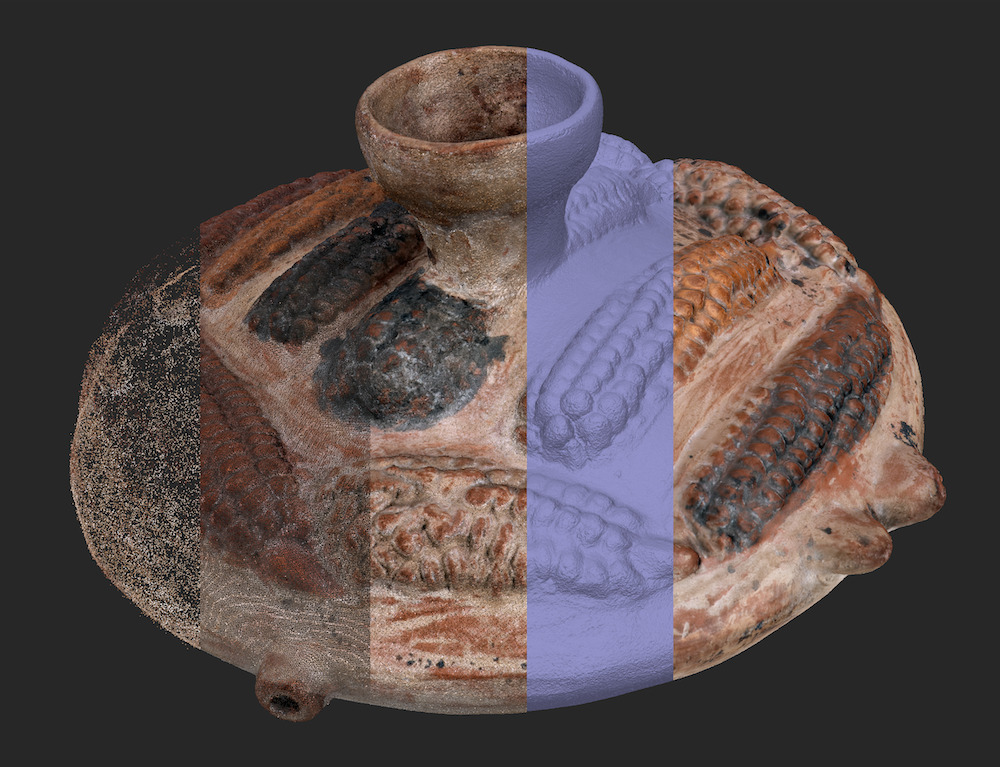

The lab’s foundational concern with change over time has led to a sustained engagement with the storied “lives of things” and to fascinating new ways of telling digital stories about works, such as in the recent Art of the Americas Interactive project.

In this extension of a Nasher exhibition on the value of the sea as a motif in the ceramics, textiles, and carvings of ancient Central and South American coastal cultures, the team developed an interactive digital platform that seeks to expand the history and analysis of these artifacts in creative ways. In all of this, though, the individual works of art take center stage. The intense interaction of digital methods, visualization, and object analysis are fundamental as a thematic core of many a Wired! project.

Banner Image: Image showing photogrammetric phases of creating a digital model. The object is a 15th-century Incan pacha in the Nasher Museum of Art’s permanent collection. Image Credit: Edward Triplett