Spaces & Systems

- Victoria Szabo

- Edward Triplett

Digital mapping and spatial analysis have become important ways to contextualize and frame the production of visual culture and art historical objects, as well as their circulation and reception. Understanding artifacts on-site—how they operate, are experienced, and change over time—aids the processes fundamental to the analysis and interpretation of their cultural and aesthetic significance. Mapping networks of influence, charting flows of goods and services, or tracking cost-paths have become recognized approaches in the field.

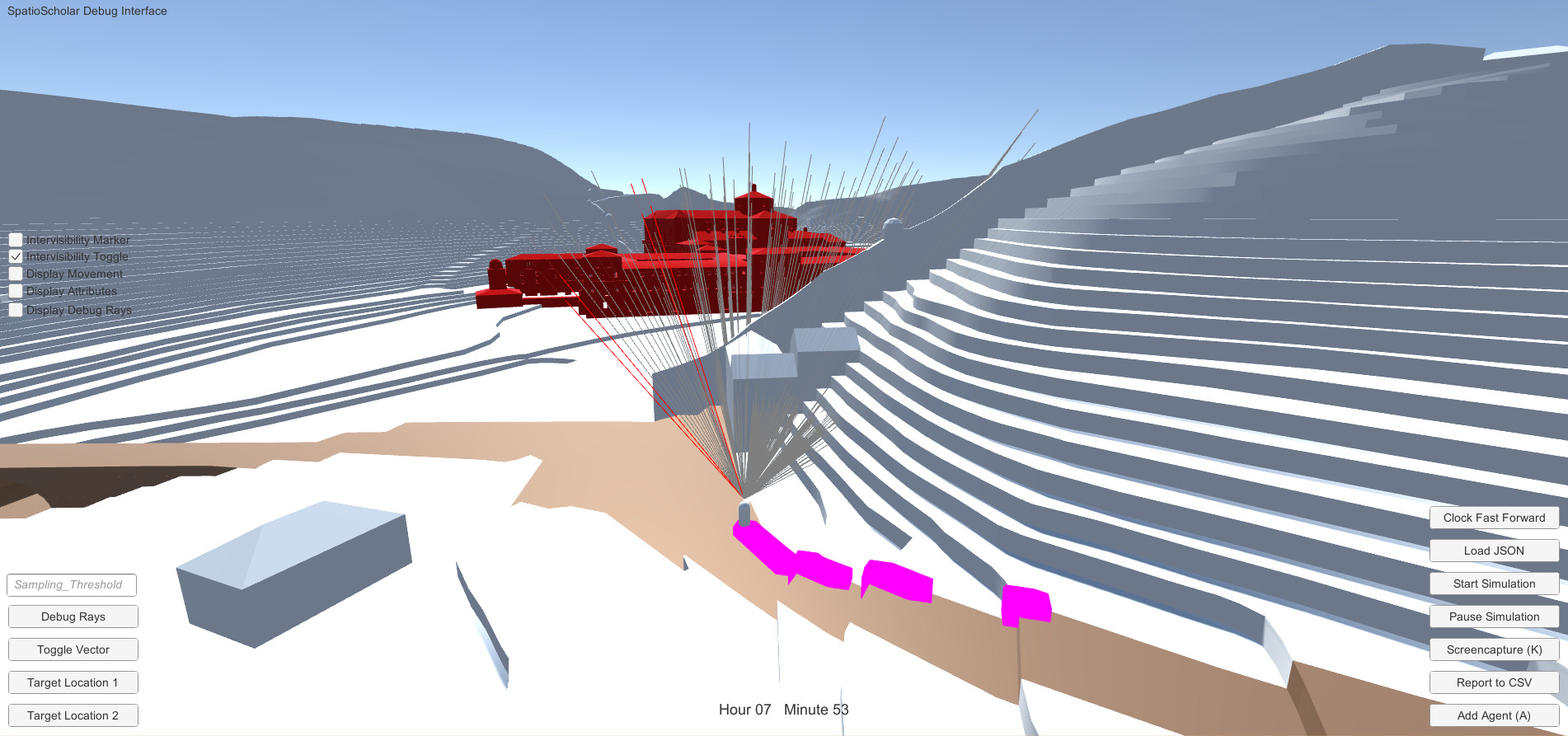

Adding a third dimension further enriches it by enabling researchers to place 3D models within such contexts, to perform viewshed analyses, and to construct spatially organized databases connected to rich collections of primary and secondary source materials. These latter benefits are not trivial as they allow researchers to aggregate their research projects and datasets, enabling the field to build more collectively than ever before. Further, by making these resources available via the web, we have the opportunity to use platforms for scaling up via integrated datasets. In addition, platforms themselves can be used for digital storytelling to reach broader publics—a complement to written scholarship.

Understanding artifacts on-site—how they operate, are experienced, and change over time—aids the processes fundamental to the analysis and interpretation of their cultural and aesthetic significance.

It should not be surprising that spatial questions were some of the first asked as the Humanities experienced a “digital turn” in the 1990s. Geography is a natural bridge-field between social, material, and environmental evidence, and GIS (Geographic Information Systems) has a firm foothold in Digital Humanities as a common system for structuring spatial data about the past and present; it bears noting that Humanities work has also informed the ongoing capabilities of these technologies, underscoring how visualizing data remains a deeply interpretive act.

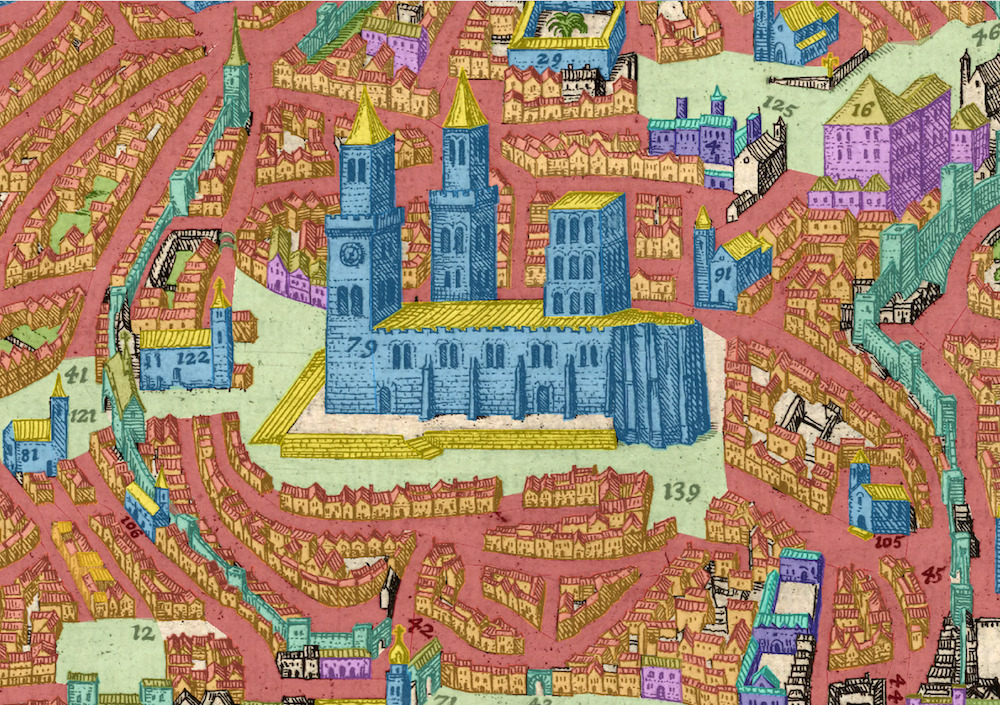

The Digital Art History & Visual Culture Research Lab is no exception in its pursuit of spatial patterns through GIS and other digital mapping approaches. Early approaches such as those of Digital Athens, The Medieval Kingdom of Sicily Image Database, and Visualizing Venice, have all had place as central to their research questions, and over the last ten years each project’s collaborators have pursued iterative, structured processes that extend the challenging work of continuously adding sources to a spatially-aware system. This tradition of place-based digital research is continued in the exploration of the local context of architecture and spaces in Building Duke, Digital Durham, Paris of Waters, and the Digital Public Buildings in North Carolina, and more broadly through Mapping German Construction, Mapping Stereotomy, and the Book of Fortresses projects.

Venice has proven to be a particularly rich subject for publicly engaged, spatial storytelling via museum exhibitions and online videos of rendered 3D scenes.

Venice has proven to be a particularly rich subject for publicly engaged, spatial storytelling via museum exhibitions and online videos of rendered 3D scenes. These projects have led to one of our most sustained group partnerships with the international Visualizing Venice research team. Alongside our partners in Italy, we have co-developed digital art and architectural history projects that rely on digital tools such as mapping, modeling, and data analysis to deepen research, open up new questions, and disseminate information through innovative presentation strategies such as exhibitions, virtual environments, and mobile applications.

An edited volume from Routledge details the results of our collaboration through a variety of case study examples. As a community, we continue to produce “hybrid” art historical scholarship not only on Venetian subjects but also on other art historical and urban contexts, such as Krakow, Athens, and Padua. While the modes of publishing our Venice research have varied considerably, each of them emphasizes close looking and reading of primary sources, a mindfulness to the socially constructed nature of space, and a commitment to pushing the boundaries of Art History and Visual Culture through additional research into ever-advancing technologies.

While the modes of publishing our Venice research have varied considerably, each of them emphasizes close looking and reading of primary sources, a mindfulness to the socially constructed nature of space, and a commitment to pushing the boundaries of Art History and Visual Culture through additional research into ever-advancing technologies.

As the Digital Art History & Visual Culture Research Lab moves forward, our spatial and place-based projects are beginning to cross lines that have unnecessarily been drawn according to technological choices. Just as it will eventually be unnecessary to add the prefix “Digital” to Art History, we look forward to the development of research that is not quickly categorized by the tools used to create it—as a GIS, CAD, or Augmented Reality project. Some of our own scholarly projects are already operating that way. Our work on space and place already moves between these methodological, but not theoretical, boundaries, and we will continue to draw from the collective variety of approaches we have used over the last ten years and to offer the broader field of Art History our insights and pathways as we move forward.

Banner Image: Edward Triplett studies a point cloud of a Portuguese fortress. Image Credit: Alina Taalman