Future Directions

- Kristin L. Huffman

- Hannah L. Jacobs

- Paul B. Jaskot

As this celebratory volume attests, the successes of students, staff, and faculty in the Wired! Lab for Digital Art History & Visual Culture have been varied, deep, and meaningful over the past ten years. Such successes lay the groundwork for, and predict, more to come as we expand our scholarly agendas, all the while attending to our fundamental commitment of integrating teaching and research at all levels. For this future, three immediate priorities come to the fore: the development of new collaborative teaching models; the integration of research projects; and the building of community. Attention to each of these aspirations grounds our decision to highlight research as the central unifying term in our new name: the Digital Art History & Visual Culture Research Lab. These points of emphasis serve as building blocks upon which we can construct a critical approach to the digital analysis of art and visual culture.

three immediate priorities come to the fore: the development of new collaborative teaching models; the integration of research projects; and the building of community.

To begin, we can pick up where our discussion of collaborative teaching left off (see Teaching). In addition to our current practices, there is a need to think more deeply about collaborative teaching not only within our research lab but also within the Humanities as a whole. Universities generally, and Humanities programs specifically, are going through yet another moment of transition in which questions of digital learning have taken center stage. Increasingly, the visual components of the digital are also being addressed as a media-specific point of analysis. In addition, the labor involved in both training students and sustaining research projects has further emphasized how crucial rethinking and extending the collaborative model may be.

How can we share teaching modules that, for example, train students to use GIS as a historical digital mapping platform? Conversely, where does the intersection lie in our classes and in our research concerning a shared question of the tension between (humanities) evidence and (computational) data? Is modular teaching a way to address these questions, and, if so, how do we make that argument in an academic environment that institutionally privileges individual labor and pedagogic structures? In sum, to promote critical digital research for Art History and Visual Culture, we must extend our current practices while also addressing the need to rethink them fundamentally in order to be critical in the first place.

How can we share teaching modules that, for example, train students to use GIS as a historical digital mapping platform? Conversely, where does the intersection lie in our classes and in our research concerning a shared question of the tension between (humanities) evidence and (computational) data?

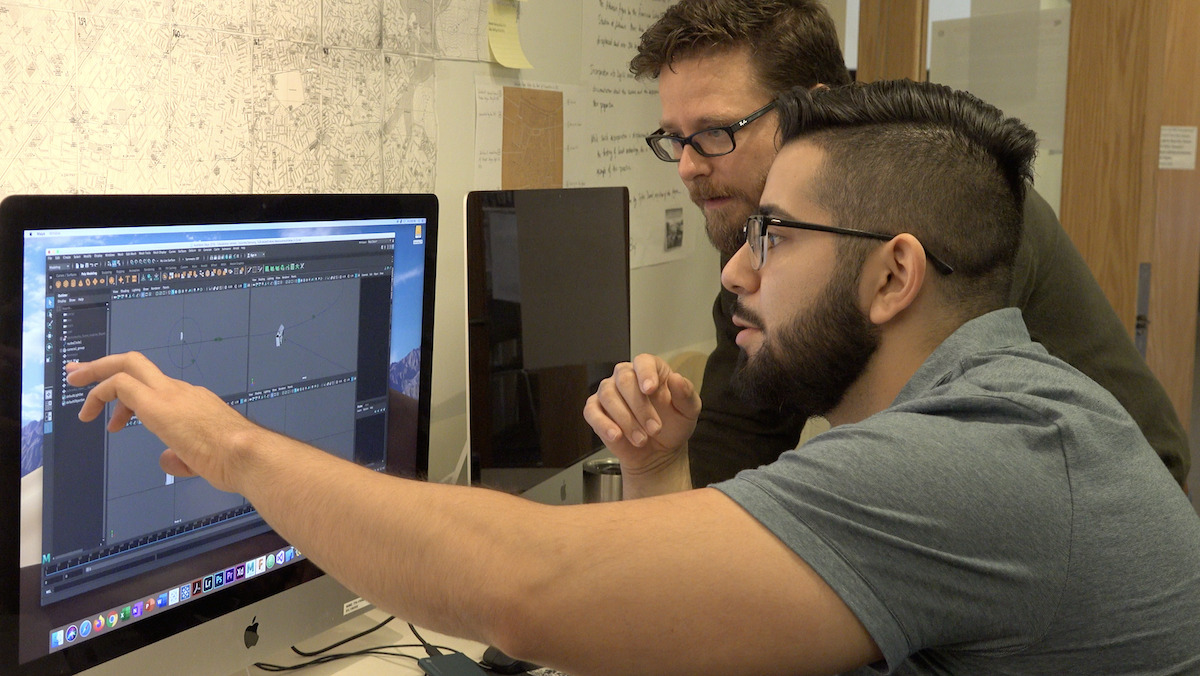

Second, our active research projects (see Project Narratives) point not only to overlapping thematic areas, but also, increasingly, to the possibility of formulating a truly integrated research agenda. This is perhaps best exemplified by the exciting potential for Visualizing Cities as a way of allowing many of our projects to speak to each other (see Visualizing Venice to Visualizing Cities). As a serious agenda, we need to start thinking about overlapping conceptual issues such as how lost architectural and social spaces are imagined/developed and how digital platforms, and their capabilities, may speak to each other in critical ways.

Can we build a truly comparative analysis of cities? What are the critical questions for this kind of work? Why does it need to engage collaborative work in both the Humanities and computational scholarship? “Interoperability” in this sense points to the multiple potential levels of integration in both digital and humanities terms. In many ways, it can be like the “grand challenges” of the sciences, i.e. a major research goal that is sustained by specific collaborative scholarly projects committed to a shared critical analysis. That is an exciting possibility, one we are eager to take on.

Can we build a truly comparative analysis of cities? What are the critical questions for this kind of work? Why does it need to engage collaborative work in both the Humanities and computational scholarship?

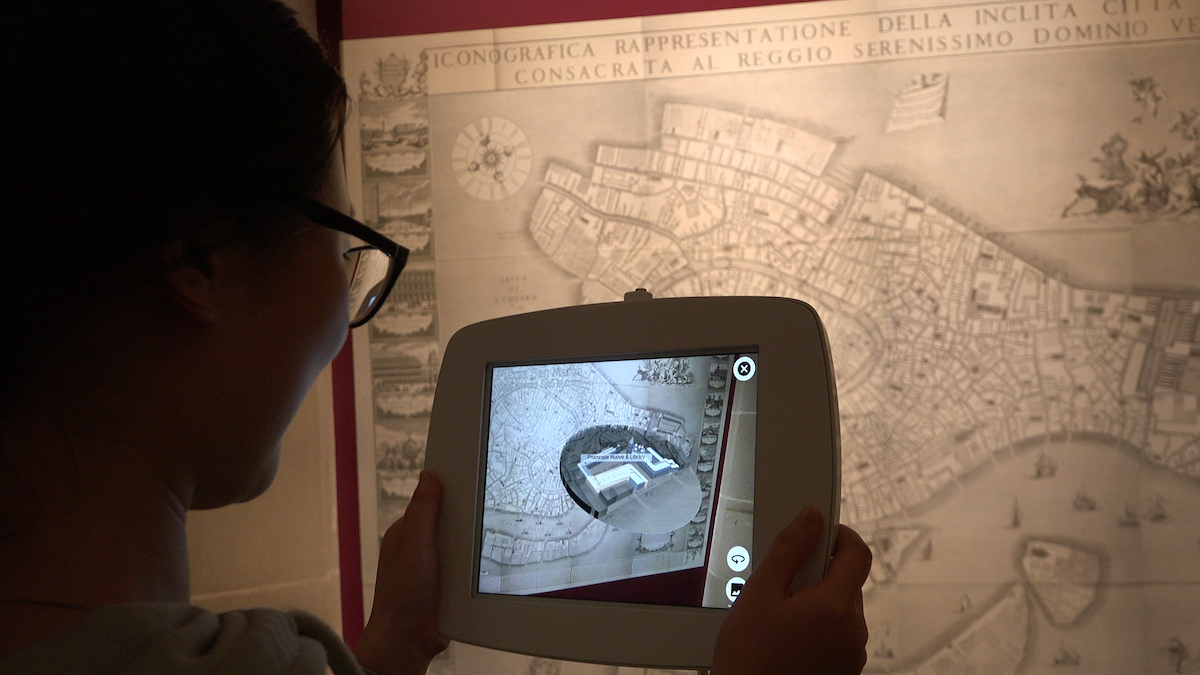

Third, we see that the future holds the possibility of a much greater expansion of our publics through our scholarly output. We have shown over the past decade that we are able to develop and sustain a true learning community; we have also shown that such community has led to public-facing work ranging from mobile applications, to websites, to databases, to exhibitions, to articles and books. But digital and cultural studies are still only at the initial stages of truly addressing broader audiences, both within and without institutions.

How, for example, do we engage with questions that are of earnest concern to our students and their post-graduate world? Are we speaking to Black Digital Humanities communities? To Feminist communities? To marginalized communities in general and to questions of access and the digital divide? Why is the digital analysis of art history and visual culture crucial to these publics, too?

digital and cultural studies are still only at the initial stages of truly addressing broader audiences, both within and without institutions. How do we engage with questions that are of earnest concern to our students and their post-graduate world?

Clearly, our current projects overlap with interests of a broad community, addressing as they do themes of gender and ethnicity, class and labor, and power and oppression, among other topics. Yet how can we help be a leader in bringing this work to an academic and non-academic public that is impactful, rigorous, and engaged? There have certainly been individual Wired! projects and outputs that have done just that. Our challenge is now, with a deeper focus on collaboration and research, to extend these project examples and to include broader communities as a whole. That seems very much a challenge worth pursuing in our next decade of work—the next exciting chapter of Duke University’s Digital Art History & Visual Culture Research Lab.

Banner Image: Point cloud of the fortress at Monsaraz by Edward Triplett.